Derivations used in rivr

Michael Koohafkan

Source:vignettes/technical-vignette.Rmd

technical-vignette.RmdIntroduction

This vignette documents the mathematical derivations for

gradually-varied and unsteady flow analysis with rivr. All

derivations are based on Chaudry

(2007). In Section 1, important definitions related to channel

geometry are discussed. In Section 2, basic concepts of open-channel

flow are discussed and one-dimensional shallow-water equations are

derived. In Section 3, gradually-varied flow is derived and the

standard-step method is discussed. In Section 4, the kinematic and

dynamic wave models for simulating unsteady flow are derived along with

the three discretization methods available in rivr.

Finally, Section 5 discusses the Method of Characteristics and its

application to boundary conditions of unsteady flow simulations.

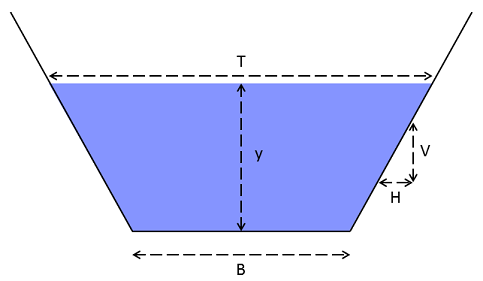

Section 1: Channel geometry relations

A channel is prismatic if it has the same slope and

cross-section throughout its entire length. The rivr

package currently supports prismatic trapezoidal channels of arbitrary

bottom width

and side slope

.

Given a flow depth

,

the flow area is then

Another important definition is the

wetted perimeter

,

which for a trapezoidal cross-section is

The hydraulic radius is the ratio of

the cross-sectional flow area to the wetted perimeter, i.e.

The hydraulic depth

is defined as the ratio of the cross-sectional flow area to the top

width

,

where

which for a trapezoidal cross-section

yields

and

Finally, the term

is related to hydrostatic pressure and is defined as the distance from

the water surface to the centroid of the cross-sectional flow area, i.e.

The definitions described above are fundamental properties related to one-dimensional open-channel flow. These relations (and their derivatives) are used extensively in the following sections to derive important flow relations and appear repeatedly in numerical solution schemes.

Section 2: Basic concepts of one-dimensional open-channel flow

The flow depth of a channel in an equilibrium state is called the

normal depth, i.e. the flow depth at which gravitational forces

(bed slope) are balanced by friction forces (bed roughness). The

rivr package expresses the normal depth via the

semi-empirical Manning’s equation

where

is the channel flow,

is the channel slope,

is the cross-sectional flow area,

is the hydraulic depth and

is a conversion factor based on the unit system used (1.49 in US

customary units and 1.0 in SI units). The expression is often rewritten

as

Where

is the channel conveyance. The normal depth

factors into the expressions of both

and

(i.e. )

and the above equation cannot be rearranged to solved explicitly for the

normal depth; an implicit (iterative) solution is needed. The univariate

Netwon-Raphson method is often used to provide efficient and precise

solutions for

.

Generally, the Newton-Raphson method is defined as

where

is the updated guess for the parameter for which a solution is sought,

is the prior guess for the parameter value,

is a zero-valued function of the parameter and

is the derivative of said function. To apply the Newton-Raphson method

here, Manning’s equation is rewritten as

and its derivative is

where

.

A related concept is the critical depth, the flow depth which

minimizes the specific energy of the flow. The specific energy is the

sum of flow depth and velocity head, i.e.

where

is the uniform flow velocity. The critical depth is then the flow depth

that satisfies

For a trapezoidal channel it can be

mathematically proved that only one critical depth exists for a given

flow rate. The critical depth can be solved using the Newton-Raphson

method with

and

where

for a trapezoidal channel. The critical depth is also the depth at which

the Froude number of the flow is unity; the Froude number is a

dimensionless measure of bulk flow characteristics that represents the

relative importance of inertial forces and gravitational forces and is

defined as

Flows are referred to as subcritical if the flow depth is

greater than the critical depth

()

and supercritical if the flow depth is less than the critical

depth

().

Flows can transition gradually from subcritical to supercritical

conditions; when the rate of variation of flow depth is small with

respect to the longitudinal distance over which the change occurs, the

river state is referred to as gradually-varied flow. In

contrast, the transition from supercritical to subcritical conditions

occur abruptly in the form of a hydraulic jump and is an example of

rapidly-varied flow. Both gradually-varied and rapidly-varied

flows can be either steady (flow is constant through time) or unsteady

(flow rate varies with respect to time). The rivr package

provides solutions for steady gradually-varied and unsteady flow

problems.

Section 3: Solutions to steady gradually-varied flow problems

The standard-step method can be used to solve the steady

gradually-varied flow profile when the channel flow and geometry are

known. Additionally, the flow depth

must be known at a specified channel cross-section; this cross-section

is referred to as the control section and the flow depth

associated with the channel flow rate

at the control section is

.

The total head

at the control section is the sum of the elevation head, flow depth

head, and velocity head, i.e.

where

is the elevation of the control section bottom relative to some datum

and

is the cross-sectional flow area at the control section. From

conservation of energy, it follows that the total head

at some downstream cross-section, referred to as the target

section, is

where

is the head loss. While the head loss term generally combines both

friction loss and form drag, the latter component is neglected by

rivr. The friction component is expressed as the average

friction slope between the control and target sections:

where

is the longitudinal distance between the control and target section.

Note that the sign of

therefore depends on whether the control section is upstream

()

or downstream

()

of the target section. Substituting these terms into the governing

equation and rearranging yields

Note that all terms on the right-hand

side of the equation are known, while

and

on the left-hand side of the equation are functions of

.

Transposing all terms to the left-hand side yields a zero-value function

of

:

This function is suitable for solving

using the Newton-Raphson method discussed previously, i.e.

where

and

Once the flow depth at the target

section is found, the target section becomes the new control section and

the flow depth at the next target section is computed, with the

algorithm “stepping” up or down the channel to a specified distance from

the initial control section. The standard-step method is accessed via

the function compute_profile.

Section 4: Solutions to unsteady-flow problems

Unsteady flow problems are generally characterized using the Shallow Water Equations, with the one-dimensional form expressed as where the first equation expresses mass conservation and the second expresses momentum conservation. Without further simplification, these equations are often referred to as the Dynamic Wave Model (DWM). The Kinematic Wave Model (KWM) refers to a simplification of the momentum equation by assuming , i.e. the momentum equation is instead expressed through the relation Both the KWM and DWM can be solved using numerical discretization methods such as finite-difference schemes. Finite-difference schemes discretize a continuous model domain into a series of nodes separated by an incremental distance . The model time domain is similarly discretized into a series of time steps separated by an incremental time . A finite-difference scheme is called explicit if the value of the variable being solved for on time step depends explicitly on the value of the variable at the previous time step . Explicit methods are advantageous because they are easier to program and implement, but are disadvantageous because they are subject to stability constraints. The stability constraint is defined by the Courant number which represents the ratio of the flow velocity to the rate of propagation of information through the model domain. The numerical solution is unstable if .

The rivr package provides an interface to one

finite-difference numerical scheme for the KWM and two finite-difference

schemes for the DWM. In addition, the DWM interface supports boundary

condition solutions using the Method of Characteristics (MOC). These

schemes are accessed via the function route_wave and their

derivations are discussed below.

Solution to the Kinematic Wave Model

The KWM finite-difference scheme implemented in rivr

requires a constant time step and spatial resolution, a known upstream

boundary condition (flow) for the full simulation time, and an initial

condition (flow) at every node. The initial water depth, flow area, and

flow velocity are calculated from the channel geometry relations, with

the initial water depth assumed to be the normal depth. At the

initiation of a new time step

,

the flow at the upstream boundary node

is assigned from the user-supplied boundary condition. The flow depth at

the upstream boundary is calculated as the normal depth for that flow,

i.e.

where the superscripts denote the

timestep. The flow at a downstream node

is computed as

where the subscripts denote the node.

The flow depth at node

is calculated using a Newton-Raphson formulation where

and

Once the flow depth is known, the

remaining geometry relations can be computed and the algorithm moves to

the next downstream node. The algorithm advances to the next time step

once all nodes are computed.

Solution to the Dynamic Wave Model: the Lax diffusive scheme

The set of equations describing the DWM are more complex than the KWM, and therefore requires more sophisticated numerical solution methods. The Lax diffusive scheme is similar to the scheme used for the KWM in terms of the model domain discretization and initialization, but requires additional computations at each node to obtain the solution.

For an internal (non-boundary) node on time step , flow values are computed through a two step process. First, averages of , , and the inertial term are computed for the node, i.e. The values for node on time step are then calculated as where . To compute the flow depth from the new area , the Newton-Raphson method is again applied where and It is clear from the derivation that unlike the KWM solution, both the upstream and the downstream boundary conditions must be known at each time step. The MOC described later provides a method for predicting, rather than imposing, the downstream boundary condition.

Solution to the Dynamic Wave Model: the MacCormack scheme

The MacCormack scheme is an advanced finite-differencing scheme that provides high accuracy for considerably coarser spatial and temporal resolutions compared to the Lax diffusive scheme. The scheme consists of a backwards-looking predictor step followed by a forward-looking corrector step. The intermediate values calculated in the predictor step are used to develop new intermediate values in the corrector step, and these calculations are averaged to obtain the final value. The predictor step computes the intermediate values at an internal node as with intermediate values of and ( and ) computed from these results. On the corrector step, new values for and are computed as The new values for time step are the arithmetic averages of the predictor and corrector step results, i.e. and . The remaining terms are then computed from these new values.

Solutions to boundary conditions: the Method of Characteristics

The DWM solution schemes provided by rivr require that

both the upstream and downstream boundary be known. Because the

downstream boundary is not known a priori under many

circumstances, the requirement would limit the utility of the numerical

schemes. The Method of Characteristics (MOC) provides a method for

predicting the downstream boundary condition at the beginning of each

time step, allowing users to route waves trhough the downstream boundary

with minimal loss of information. In addition, the method also allows

the user to specify both the upstream and downstream boundary conditions

in terms of either flow or depth, and allows specification of sudden

cessation of flow, i.e. closure of a sluice gate at the upstream or

downstream boundary.

MOC is a well-known concept with application to a wide variety of numerical problems; the general theory is not presented here. It can be shown that the upstream boundary condition (node ) on time step can be defined as where and As seen from these relations, the flow velocity and depth at the upstream boundary on any time step are related to the initial conditions (i.e. ). The downstream boundary condition (node ) is similarly expressed as where and Therefore given either a flow or depth on timestep , the upstream boundary condition can be computed as long as the initial conditions are known. This is a notable improvement over the normal-depth assumption of the upstream boundary condition employed in the KWM. Flow can be routed through the downstream boundary by assuming the gradient in flow or water level between the downstream boundary and the nearest internal node is zero (i.e. or ). This results in “smearing” the solution across the downstream boundary but is often still preferable to direct specification of flow. Specifying the downstream boundary as a constant water depth representing i.e. a lake or reservoir water level may also be appropriate under many circumstances. When flow is specified at e.g. the upstream boundary, flow depth and area are solved simultaneously using a Newton-Raphson scheme where and Note that if the flow depth can be solved for directly, and if depth is supplied then the flow can be solved for directly. The solution method for the downstream boundary is analogous, noting that the sign of the second term in and the corresponding term in its derivative are reversed.